Dustin Brown’s primary line of work is being a north-south, imposing but durable power forward capable of carrying the puck into the offensive zone and finding that sweet spot in front of or near the attacking net.

A secondary line of work, some 10 years from now, could be a writer, or a commentator, or someone in a position in which rational, thoughtful analysis can be broadcast to those keen on learning something they hadn’t previously known. On the Los Angeles Kings, there is no better source for weighed, balanced analysis of the team and the state of the game, and Brown shares pithy observances with accountable assurance. For the sexy, viral quote that can fit in 140 characters, there are others to seek out. To gain an understanding of what someone has learned as his 1,000th NHL game approached, few can dispense wisdom as lucidly as Brown.

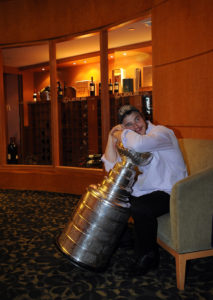

That game is here. It’s tonight against the Colorado Avalanche, and if there’s something that Brown has consistently shared with those who’ve asked him questions about his 14-year, 999-game tenure to date, it’s that he credits those around him and takes pride in the sum-of-all-parts that has resulted in two Stanley Cups, a conference finals appearance, and, ultimately, blueprints for an expanded section of retired jerseys above the end in which the Kings shoot twice.

“The reason I’m able to play 1,000 games is because I played with a group of guys for a very long time and have been successful,” he said. “If you could rewrite history and we don’t win in 2012, maybe even Kopi’s not here right now. Maybe I’m not here. Maybe Quick. Everything changes, because success breeds success. I think we’ve had a lot of players set a lot of organizational milestones, records, and it’s a result of a collective group of players that has been really good for a decade now. It’s been less individual than it might seem. 1,000 games for me is a result of playing with really good players for the last 600.”

Brown, and Jonathan Quick, who played in his 500th game earlier this season, are the first members of the two-time Stanley Cup-winning core to reach significant personal milestones. With them are Anze Kopitar, who will play his 876th game as a King tonight, and Drew Doughty, who will play his 724th. All are homegrown players who were not incubated by the type of reinforced-steel culture that many of the players have referenced during and after their competitive rise this decade.

“My first few years, it was a turnstile in here. We had new faces every day, every game, and then things started to change around ‘08, ‘09, ’10,” Brown said. “What’s more incredible, me playing 1,000 games, or me playing 800 games with two or three other players in this room?”

Before tonight, the only other player to have played his first 1,000 games as a King was Dave Taylor, who played 1,111 with Los Angeles and selected Brown as the team’s general manager in 2003.Since then, Brown has wasted no time in reaching 1,000 games as a 33-year-old. He made his debut one month shy of his 19th birthday, spent the following season on a loaded Manchester Monarchs team coached by Bruce Boudreau during the NHL’s lockout, and since returning to Los Angeles in 2005, has never missed more than four games in any season. He has appeared in at least 80 games eight times, representing a remarkable run of health and durability for such a wrecking ball of a player – and one who appeared in 81 playoff games between 2009 and 2016. He will become the 48th player in NHL history to play his first 1,000 games for one team.

“I mean, he plays hard, and he plays every night. He doesn’t miss games,” John Stevens said. “He’s as tough of a competitor as you’re going to find, but he plays a heavy, hard game and it’s not very often that he misses a game. He’s been a big part of the identity of the Los Angeles Kings for a long time.”

It’s an identity he helped create. The Kings have been known as a “big, heavy” team, a label affixed from the outside but one that was more or less accurate. Brown’s play, even when his scoring dipped over the last several seasons, has been particularly representative of the team’s systems. He’s also highly detail oriented and intelligent, so the structure that the team employed under Terry Murray, Darryl Sutter and now Stevens was lifted by his more nuanced contributions. With his emotional capacity, and the intangible leadership characteristics also inherent in his longtime teammates, that culture has been sustained and is particularly apparent during a 21-10-4 start to a season that was not expected to be a revival of the team’s recent zeniths.

“The fact that we have the same faces in a lot of these stalls is I think a big part of whatever you want to define as culture,” he said. “It’s a group of guys that have figured out what works and what doesn’t work and have had success, and also that we haven’t had success and want it back.”

“But I think ultimately it comes down to guys in the room sticking together, and to be able to stick together, you’ve got to win and figure that out. We’ve done that, and now it’s trying to find that again. It’s really hard to describe, really, but there are a bunch of guys in here that have won and we know what it means to win, and it’s trying to pull everybody into the idea of what could happen when we play the way we’re supposed to play.”

He wasn’t grown through a culture of success in his early seasons, when he was permitted to compete with 29 other teams for a Stanley Cup but not legally allowed to drink out of it. There were some great leaders on those early teams – “Guys like Lappy [Ian Laperriere] and Matty Norstrom, they made a big difference,” Brown said – but none who had won together in Los Angeles. Younger players on the current Kings roster are surrounded not just with character players, but character players who have won championships.“I just saw Lappy in Philly,” Brown said. “He was me for Dewey [Drew Doughty] when I was younger. I didn’t room with him, but I was 18. The team was different when I was 18. Dewey was 18, but we had some 19, 20, 21. When I was 18, the next closest consistent player was Aves [Sean Avery], and he was 23, 24. So there was a big gap. I was closer [in age] to Luc’s kid than I was to Luc.”

Drew Doughty, on the other hand, was able to rely on a wider net of leadership as part of a group that would go on to win Stanley Cups in 2012 and 2014. Doughty, who also credited Matt Greene and Sean O’Donnell with softening his professional maturation during his early NHL years, still looks back on the friendship he built with Brown when the two were roommates on the road.

“Obviously, the only thing that is better about not having a roommate is, you know, not having a roommate,” Doughty said. “You can buzz around naked in your room and it doesn’t matter.”

That’s very funny, and it’s certainly in line with Doughty’s ethos of playing hard and having fun on the ice, and being remarkably blunt and honest off of it, but the raw testimonial he also shared had greater depth. Taking two and a half minutes to answer a question about what he misses about rooming with Brown – the CBA effectively eliminated road roommates for players beyond their entry-level contracts beginning in 2012-13 – Doughty looked inward and noted how Brown was responsible for helping him grow into a professional.

“I was young in the league and it was not that I needed someone to talk to, but it was just nice that basically after every game, I would tell him, ‘this is what I felt about this.’ Like, ‘how can I do better at this?’ He was always there to talk to me about it, and as a young guy in the league, I think you kind of need that, because there are so many ups and downs throughout the season both as a team and personally, and it’s an emotional rollercoaster, really,” Doughty said. “I wasn’t used to having those emotional rides because I was just so dominant when I was younger. When you kind of come in, you need that. It’s almost like a shoulder to cry on. You’re not crying, but that’s what he was for me. And he taught me the ropes, taught me what it was like to be a pro, taught me what it was like to be a good teammate – and not that I was ever not a good teammate, but there were definitely aspects of my personality and stuff like that that weren’t good for the team. He helped me with all those things.”

Both were first round draft picks that made their NHL debuts as late-birthday 18-year-olds out of the Guelph Storm program. But even if the similarities were surface-level, and even though Doughty was a brash teenager while Brown was becoming more comfortable as team captain, it was the start of a friendship that carried significant importance.

“I always looked at Dewey as a little brother, really,” Brown said. “Just made sure he had my coffee in the morning.”

His presence, and the presence of players like Marian Gaborik, who will be honored tonight for reaching the 1,000-game milestone last Friday, help ease the comfort younger players face when joining a team in such a highly competitive league.

“It doesn’t matter who’s in your locker room, whether you’re talking about Doughty and Kopitar or Forbort and MacDermid, [Brown] treats everybody probably the way you’d want to be treated,” Stevens said. “He’s got a real good pulse on the locker room, and he’s a really important guy in the room. He has a good relationship with the young guys. They feel comfortable with him. I think he makes them feel at home in a quiet way. Maybe it comes from having four young kids, I don’t know, but he’s got a couple more in the locker room to take care of. But I think he’s been a great influence for those young guys.”

This is Brown’s individual moment, a major personal and team milestone. It should not be lost or cannibalized among the accomplishments of others. Brown has been literally pained by team hardships in recent years including a volatile relationship with Darryl Sutter and, in the summer of 2016, the transfer of the captaincy from him to Kopitar, one of his closest friends.

But it is impossible to talk about Brown accurately without acknowledging the context of his maturation in Los Angeles, and how his career has been shaped by influential veterans, how he grew alongside other team-drafted and developed players, and how they collectively reached the top of the hockey world twice while he was the captain of the team and a conduit between the players and the coaching staff and management.

Or, a conduit between captain and captain.

“I’ve always leaned on him if I needed to,” Kopitar said. “He was always happy to help and give some pointers and talk about stuff that made it easier for me.”

There’s a lot that he’s taken in, dished out and absorbed during his 999 NHL games, but as much as he always appears to have a firm handle on each situation, and can break plays down and articulate his and the team’s efforts and labors, there’s still an open end to the story. He feels great on the ice. With 28 points in 35 games, he’s on pace to easily break the marks he set over the last four seasons. He’s still a very effective player who cited Jaromir Jagr playing into his mid-40’s as an example for the amount of hockey he feels is left in his career. “In order for us to be successful, he’s got to be on top of his game, and that’s what he’s certainly shown,” Kopitar said. “I’m really happy for him that he has a year that he’s having right now.”

“I’m still learning,” Brown said. “33. 1,000 games. I’ll probably learn something new [Thursday] night.”

Elsa/Getty Images. Front row: Milan Michalek, Zach Parise, Ryan Suter, Thomas Vanek, Dustin Brown. Second row: Nathan Horton, Eric Staal, Andrei Kostsitsyn, Marc-Andre Fleury

-Lead photo via Dave Sandford/NHLI

Rules for Blog Commenting

Repeated violations of the blog rules will result in site bans, commensurate with the nature and number of offenses.

Please flag any comments that violate the site rules for moderation. For immediate problems regarding problematic posts, please email zdooley@lakings.com.