As we all make the most of our time in quarantine and venture towards the reopening of businesses and recreation, so too does Marián Gáborík in his hometown of Trenčín. Covid-19’s impact in Slovakia was diminished by a decision to close borders and institute a national lockdown and ban on public gatherings before many European countries, and as a result the country with the lowest per-capita mortality rate in Europe eased social restrictions last week.

There are still smaller, localized flare-ups, but “we’re in the single digits the last 10 days or so,” Gáborík said about the decreasing cases.

Trenčín, a town with a large stone castle perched atop a massive rock on which a second century inscription boasts of a Roman legion’s conquest, is a city of 55,000 that represents Slovakian’s (hockey) frontier. 75 miles northeast of Bratislava and virtually adjacent to the Czech border, it’s also the home of Marián Hossa and Zdeno Chara, and to some degree is similar to Örnsköldsvik, Sweden, a cradle of Swedish hockey culture and the hometown of Peter Forsberg, or Jaromír Jágr’s native Kladno. Along with hockey-mad Košice, it’s a de facto Slovakian hockey capital where Arena Mariana Gáboríka is a short walk from HK Dukla Trenčín’s home rink, renamed to Pavol Demitra Ice Stadium in 2011 to honor the ex-King and fellow countryman after his tragic passing in the Lokomotiv disaster.

Gáborík’s rink – a project he funded and spearheaded upon graduating from his entry-level contract with Minnesota – is a major emblem of both local and personal pride that affords children and families similar structure and resources that he received as a child. Making a point to search out the positive whether in quarantine or daily life, Gáborík directed renovations at the rink over the past two months, defrosting the ice for the first time in 12 years. “We did some maintenance,” he said of the facility that also hosts his hockey school and a small hotel. “We painted, re-did the dressing rooms and fitness center and just took care of the ice surface and the concrete. It’s all done, we’re just waiting for the green light to hand it off, so we’ll just see when it is.” Earlier that day he’d already taken a call to start planning out what his annual hockey camp would look like with added health measures. “We still want to do the five terms, five weeks of it. We’ll see if we’ll be able to start on time. We usually start in July. We hope for that, but obviously it’s still hard to say. I mean, I hope so.”

Gáborík has and will continue to spend his time well in suspended animation. He remains under contract with Ottawa for another season but hasn’t played since March 22, 2018, 16 games after his trade from the Kings and two weeks before he underwent back surgery. There’s always the benefit of having been wonderfully remunerated, but Ferraris, especially those with NHL horsepower to the tune of 407 goals in 1,035 games – don’t want to remain in the garage. They want to play, and if they’re not consistently surrounded by teammates amidst the highly regimented, structure-driven itinerary that has guided their NHL careers, their minds will naturally wander.But he’s poised to transition smoothly to his post-playing career, whenever that date technically arrives. This was easily foreseeable. Among the most well-known figures in Slovakia, the 38-year-old is easygoing and unrestrictive and maintains a level and positive mindset that made him a popular figure among teammates.

That laid-back outlook is what he brings to Boris a Brambor, a podcast he began last year with ex-Thrasher Boris Valábik that has risen to become among the most popular – and perhaps the most influential – podcast in Slovakia.

“It’s a good mix. We have a great chemistry,” Gáborík said. “He’s more of a serious guy on a podcast, and I’m throwing out a couple jokes and just being me – sometimes a little funny.”

That’s coming from Brambor, Gáborík’s nickname among Slovakian friends. Bestowed phonetically upon his brother, Brano, it was eventually inherited by Marian himself. (It should also say a lot about his character that friends supplied him with a variety of endearing nicknames – whether Ferrari, Brambor, or from his time in Minnesota, Cookie Monster.)

Conversations in Slovakian or any language always have the potential to lose context in translation, but you can get the jist of one of B&B’s most popular recurring segments, Sex pred zápasom? It translates directly to “sex before the match,” and it’s been a good icebreaker. “Every time we’re doing a story with somebody, we ask them that, so it’s a little theme that’s usually in every podcast,” he said. “We’ve just been going from athletes to celebrities here, some musicians. Because a regular interview, you’re doing it on TV or radio, everything is kind of on the surface. We’re just trying to go deep and really dissect everything and just have a loose atmosphere like we were having a coffee or we were in a bar or wherever. We’re just trying to comfort people, and the good thing is it’s not live, so if somebody doesn’t like something, it can be cut.”

That doesn’t exclude them approaching newsworthy topics. To the contrary, perhaps the most important headlines the podcast has drawn – and it has drawn quite a few – were covering B&B’s reaction to the Tipsport Liga terminating player contracts when the coronavirus forced Slovakia’s national league to cancel play. According to one player, second-place Slovan Bratislava hadn’t paid its players since January; those players then lost out on an opportunity at a championship when two members of a panel appointed Banská Bystrica, which finished two points ahead of them in the standings, as league champions. A unanimous decision was not necessary, but the panel’s vote was conducted in the absence of Miroslav Šatan, the third figure of the three-member panel and, importantly, the President of the Slovak Ice Hockey Federation. He was reportedly at home in quarantine and unaware of the vote at the time, which resulted in Banská Bystrica and third place Košice refusing to accept silver and bronze medals.

Unlike the Czech national league, players competing in the Slovak Extraliga, which formed in 1993, do not currently have a players’ union, and Gáborík was a figure in a grassroots swell to create one this spring. While B&B’s guest list boasts a murderer’s row of golden generational figures like Ľubomír Višňovský, Ladislav Nagy and Peter Bondra, it was actually that trio’s 2002 World Championship gold medalist teammate Richard Lintner, the CEO of the company that administers the Extraliga and a member of its three-person panel, whose direct interrogation by Gáborík and Valábik drew significant notice in the aftermath of the league’s shutdown. “A lot of players got fired all of a sudden,” Gáborík said. “It was sad to see. Obviously in this crisis there are a lot of different people that have worse problems than all these guys, but we’re hockey players and are going to do something to help our occupation and try to support that.”

Few conversations on the podcast were as confrontational. None talk politics. Rather, most episodes are lighthearted, occasionally influenced by other hockey podcasts. Valábik, an Extraliga television analyst, would listen to TSN’s Jay & Dan podcast featuring Jay Onrait and Dan O’Toole during his commutes, and approached Gáborík with the content idea while they were shooting YouTube videos at the beginning of the Extraliga season.

Recent episodes had Tomas Tatar, “and that was big,” Gáborík said, as well as Hossa, Nagy, biathlete Paulína Fialková and several celebrity musicians. Gáborík estimates that listens are down by 15% due to quarantining restrictions, but B&B is still the second most popular podcast in Slovakia, one that now features a production team and branches into marketing and merchandising. He hinted at an English version of Boris a Brambor because of their demand. “We’re loving it, and we’ve also made some business out of it, I would say,” he said.

“We started in October, and not even six months later we had a million [listens]. We’re doing it once a week, we’ve got two sponsorships with a bank and a betting company here. We started to do some merchandise – B&B merchandise. But mostly we’re having fun and we have great people that work with us and are helping us cut it and [familiarize us] with the guests that we don’t know as well. It’s me and Boris and three other guys that are setting up the recordings, and we haven’t stopped even after the coronavirus came, so we’re doing it over the internet, doing it that way.”

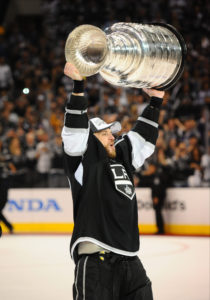

Among the positives Gáborík found in quarantine was the leisure to watch 2014 playoff games for the first time. He’d seen highlights plenty of times, but this was the first time he’d watched the games from start to finish, something he enjoyed doing alongside his wife. As it turned out, he was a lot more nervous than she was. “From that perspective, it was way easier to play the game – you’re not as nervous as watching it.”

He also spoke about one of the most thrilling 12 minute and 48-second stretches in LA Kings history, one in which he scored a game-tying goal, a game-winning goal and a first goal at Anaheim between Game 1 and Game 2.

Marián Gáborík, on his three-goal stretch against Anaheim, and what still resonates from that series:

Everybody was so pumped up after we won the San Jose series. It was a quick turnaround, which was big for us to go play Anaheim right away and not have to travel. It was crazy. I have goosebumps just talking about it. I mean, three goals within what, like three minutes, when you think about it? Not three minutes, but three different parts. It was crazy. The first one was kind of lucky. The second one was pretty much just how I scored all the goals – driving the net, being at the right spot at the right time – and the third was kind of iconic for me from early days of my career, I guess – and a great dish by Kopi. We just hit it off. Actually, I just put it on stories on Instagram – they [aired games] on Nova Sport, the Czech channel. It was on TV every day for the past five days – they were playing our series. I was watching with my wife on TV, and it was crazy, because I’d never really seen the games, right? I saw highlights, I’d never really watched the games. I was still nervous. I knew what was going to happen, when it was going to happen, but wathicng I was nervous, I was sweating, my heart was pumping. It was like I was watching a game not knowing what was going to happen, but I knew what my parents, my friends and family got to experience when they watched it live, you know?

Gáborík, on the team’s focus during its come-from-behind, Game 7 win in Chicago:

They got up 2-0 pretty quickly. I think we gave up two goals, and Sharp’s goal from the right side made it two goals again. We just had an attitude we never stopped fighting like we had against San Jose. Coming to overtime, it was just keep playing our game. Nobody had negative thoughts. Everybody was positive. Nobody was thinking, ‘OK, what’s going to happen after the game if we win?’ Having already celebrated winning the finals, everybody was present and focused. It was crazy. When Marty [shot the puck], we didn’t know if it was in, or if it went off Stolly or somebody. Eventually it went off their guy. Being in the locker room after the game, sitting on the table, I realized “I’m going to the Final against New York.” It’s hard to describe those feelings, but it was amazing.

Rules for Blog Commenting

Repeated violations of the blog rules will result in site bans, commensurate with the nature and number of offenses.

Please flag any comments that violate the site rules for moderation. For immediate problems regarding problematic posts, please email zdooley@lakings.com.